Afro-Cuban culture, Blog, Cuba, Cuban Jazz, Latin Jazz, Puerto Rico, The Cuba-US connection, Video and audio

This montage of the October 23 Benefit for Puerto Rico at Poisson Rouge (the old Village Gate) was created and contributed by the very talented Garbriel Moreno of Tableaux Multimedia.

Select video of the actual concert will be coming soon. Watch for it here.

Meanwhile…

Jazz and Latin music have been brothers for as long as jazz has been an art form

Jelly Roll Morton laid it out:

“If you can’t manage to put tinges of Spanish in your tunes, you will never be able to get the right seasoning, I call it, for jazz.”

In 1930, Don Azpiazu knocked down the doors of American popular music with The Peanut Vendor.

Machito and his musical hermano (and real life brother-in-law) Mario Bauzá kicked it into high gear with one of the greatest big bands ever to rock a jazz stage.

Then in 1947, thanks to an introduction by Bauzá, bepop pioneer Dizzy Gillespie teamed up with Chano Pozo to create a model for collaborations between Latin and Jazz musicians that has been going strong ever since.

Started by the Mario Bauzá’s rhythm section and jazzman Sonny Fortune, Monday night at the Gate was THE place to go with crowds lining up around the block to get in.

On Monday October 23, 2017, in support of the people of Puerto Rico, many of the giants who were part of this legendary time came back for a once-in-a-lifetime, never-to-be-repeated reunion with Bobby Sanabria‘s big band Multiverse.

Over time, we will be releasing video of this historic event.

Meanwhile, this is what it’s all about…

No sightseers please. We need givers right now. Please read how you can help.

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

Afro-Cuban culture, Blog, Cuba, Cuban Jazz, Latin Jazz, Puerto Rico, The Cuba-US connection, Video and audio

A preview of some of the magic you’ll see at the Benefit.

Conga master Candido (age 96) surprises the crowd with his rarely-seen bass and cowbell skills.

Bobby Sanabria explains what’s in store for the audience this Monday, October 23 at Poisson Rouge in New York City: an unprecedented meeting of Jazz and Latin superstars to benefit Puerto Rico.

Details

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

Afro-Cuban culture, Blog, Cuba, Video and audio

A stage performance by the group Osain del Monte.

The drums they are playing are called Batá.

There are four major African cultural and spiritual influences alive and thriving in Cuba today: Palo (Congo), Abakuá (from the Carabalí), Arará (from Dahomey, now Benin), and Regla de Ocaha, also called La Regla de Ifá or Lucumi, most widely known as Santeria (Oyo Empire, now Nigeria.)

We’ve looked at two: Palo and Abakuá.

In this post, we will look at Santeria.

First, a highly relavent quote which I’ve heard on tape, but have never seen in text on the Internet. Here it is for the first time in print:

“Playing a musical instrument is a form of worship – and I’ve been worshipping all my life.”

– John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie

This quote explains more about the African approach to music than any hundred volumes can (though I think Johan Sebastian Bach would be in agreement with it too.)

Santeria

Santeria is a serious subject that deserves serious consideration. A book that many hold in high regard and was written by an Oba (an experienced Santeria priest) is “Walking with the Night” by Raul Canizares. The book comes with a brief glossary and bibliography.

Santeria originated in what is now Nigeria and is the most widespread of the African cultural and spiritual traditions in Cuba.

The name of this performance is “Osain del Monte.” It’s named after one of the orishas of Santeria in Cuba, Osain (in Africa “Osayin”), the orisha of healing herbs and all plants and vegetation.

Orishas are deities, spirits, gods, saints who mediate between human beings and God Almighty.

There are many. Here are just a few of the ones that made it from Africa to Cuba:

Eleguá, Lord of the Crossroads (and a playful trickster). Red and black.

Ogún, The Lord of Metals. Green and black.

Yemaya, The Owner of the Seas. Blue and white.

Ochún, The Queen of the Rivers. Gold.

Changó, Lord of Fire and Lightning (and music and drumming). Red and white.

Orula, Master Diviner. Yellow and green.

Babalú-Ayé, Disease and healing. Walks with a crutch.

Obatalá, Creator of the world and all humans. White.

Oyá, The Owner of the Wind. Rainbow.

Each orisha has its own costume and array of elaborate rhythms and songs and movements and dance. In Africa, they even had their own drums, but in Cuba all the orishas use Changó’s drum.

Based on the color hints in the short list of orishas above, see how many you can identify in this performance.

The Oyo Empire

Santeria originated in the Oyo Empire (Yorubaland), now within the boundaries of Nigeria.

What was this kingdom like before it was destroyed?

First, it was the most urban of traditional African cultures.

Here’s what the remnants looked like to the American missionary, R.H. Stone who visited the Yorubaland city of Abeokuta in the middle of the 19th century:

What I saw disabused my mind of many errors in regard to Africa.

The city extends along the bank of the Ogun for nearly six miles and has a population of approximately 200,000…

They were well dressed and industrious providing everything their physical comfort required.

The men are builders, blacksmiths, iron-smelters, carpenters, calabash-carvers, weavers, basket-makers, hat-makers, traders, barbers, tanners, tailors, farmers and workers in leather and morocco…they make razors, swords, knives, hoes, bill-hooks, axes, arrow-heads, stirrups…

…Women…spin, weave trade, cook, and dye cotton fabrics. They also make soap, dyes, palm oil, nut-oil, all the native earthenware, and many other things used in the country.

Vast looting and destruction by Europeans removed much of the evidence of this civilization (much like the Roman’s calculated eradication of Carthage), but the statuary that survives shows that this was a very sophisticated society indeed – as does its singing, drumming and dance which lives today.

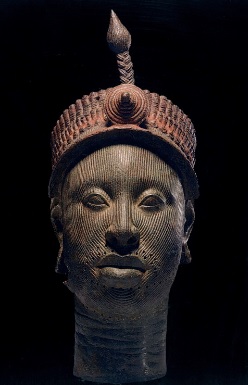

Bronze sculpture of 14th century Yoruba ruler, City of Ife (Nigeria)

Bronze sculpture of 14th century Yoruba ruler, City of Ife (Nigeria) Terracotta head 12-14th century

Terracotta head 12-14th century

City of Ife (Nigeria)– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.

Go to Cuba with Jazz on the Tube as your guide:

Click here for details

Afro-Cuban culture, Blog, Cuba, Cuban Jazz, Latin Jazz, Puerto Rico, The Cuba-US connection, Video and audio

Interview

Download the mp3 here

Restoring the Bronx-Cuba Music Connection

August 2017, Jazz on the Tube brought Havana jazz educator Camilo Moreira to New York City and the Bronx to experience US jazz and meet his Latin jazz “uncles” and “cousins” in the U.S. first hand for the first time. (Camilo has been up before but always with heavy work loads that didn’t permit him to do any of his own explorations.)

Bobby Sanabria kindly took us around the Bronx to learn about the mostly unknown history of this most important and under-appreciated hotbed for musical innovation in America. We also hit the clubs and other resources like the Performing Arts Library at Lincoln Center, the Bronx Music Heritage Center and the Schomburg Center in Harlem.

The Bronx: One of the most innovative music communities on earth.Coltrane, Monk, Miles, Dizzy, Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins, Herbie Hancock, and others all found audiences in the borough’s vast network of live music venues as did Machito, Tito Puente, Tito Rodriguez, Celia Cruz, Mongo Santamaria, and many others.

The Bronx: One of the most innovative music communities on earth.Coltrane, Monk, Miles, Dizzy, Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins, Herbie Hancock, and others all found audiences in the borough’s vast network of live music venues as did Machito, Tito Puente, Tito Rodriguez, Celia Cruz, Mongo Santamaria, and many others. Bobby Sanabria, Mike Amadeo, and Camilo at Casa Amadeo. Amadeo, proprietor of the oldest Latin music store in the Bronx, is the author of over 300 songs written for and performed by the likes of Celia Cruz, Danny Rivera and Cheito Gonzalez.

Bobby Sanabria, Mike Amadeo, and Camilo at Casa Amadeo. Amadeo, proprietor of the oldest Latin music store in the Bronx, is the author of over 300 songs written for and performed by the likes of Celia Cruz, Danny Rivera and Cheito Gonzalez. An original mint condition disk of the super hit of 1930, “El Manisero” (The Peanut Vendor), the first million seller in Latin music history.

An original mint condition disk of the super hit of 1930, “El Manisero” (The Peanut Vendor), the first million seller in Latin music history. The remaining facade of one of over one hundred live theaters, concert halls and night clubs that used to dot the Bronx.

The remaining facade of one of over one hundred live theaters, concert halls and night clubs that used to dot the Bronx. The South Bronx in 1976 when presidential Jimmy Carter candidate visited for a photo op. Devastated by highways built through the community, bank redlining, the heroin epidemic launched by the Vietnam War and calculated government neglect, this immigrant and working class community was plunged into social and economic chaos. The sense of unease felt by the outsiders, including New York City’s mayor at the time, is palpable in this photo.

The South Bronx in 1976 when presidential Jimmy Carter candidate visited for a photo op. Devastated by highways built through the community, bank redlining, the heroin epidemic launched by the Vietnam War and calculated government neglect, this immigrant and working class community was plunged into social and economic chaos. The sense of unease felt by the outsiders, including New York City’s mayor at the time, is palpable in this photo. The Puerto Rican community fought back against long odds on many fronts. The “Three Sisters” (Las Tres Hermanas) Evelina Lopez Antonetty, Lillian Lopez, and Elba Cabrera took leadership roles in the arts, libraries and the public school system demanding and winning equal treatment for the Bronx.

The Puerto Rican community fought back against long odds on many fronts. The “Three Sisters” (Las Tres Hermanas) Evelina Lopez Antonetty, Lillian Lopez, and Elba Cabrera took leadership roles in the arts, libraries and the public school system demanding and winning equal treatment for the Bronx. Bobby shares some details of the history of the Bronx’s Puerto Rican community at the Bronx Music Heritage Center where he is Co-Artistic Director.

Bobby shares some details of the history of the Bronx’s Puerto Rican community at the Bronx Music Heritage Center where he is Co-Artistic Director. Camilo stands with Las Tres Hermanas in front

Camilo stands with Las Tres Hermanas in front

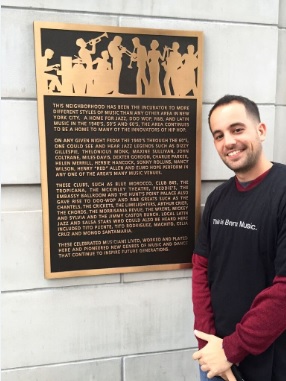

of the Casita Maria Community Center.Here’s the text of the plaque Camilo is standing in front of in the first picture:

This neighborhood has been the incubator to more different styles of music than any other area in New York City. A home for Jazz, Doo Wop, R&B, and Latin music in the 1940’s, 50’s and 60’s, the area continues to be a home to many of the innovators of Hip Hop.

On any given night from the 1940’s through the 60’s, one could see and hear jazz legends such as Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Maxine Sullivan, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, Charlie Parker, Helen Merrill, Herbie Hancock, Sonny Rollins, Nancy Wilson, Henry “Red” Allen and Elmo Hope perform in any one of the area’s many music venues.

These clubs, such as Blue Morocco, Club 845, The Tropicana, The McKinley Theater, Freddie’s, The Embassy Ballroom and The Hunt’s Point Palace also gave rise to Doo-Wop and R&B greats such as the Chantels, The Crickets, The Limelighters, Arthur Crier, The Chords, The Morrisania Revue, The Wrens, Mickey and Sylvia and the Jimmy Castor Bunch. Local Latin Jazz and Salsa stars who could also be heard here included Tito Puente, Tito Rodriguez, Machito, Celia Cruz and Mongo Santamaria.

These celebrated musicians lived, worked and played here and pioneered new genres of music and dance that continue to inspire future generations.

More about Camilo Moriera

More about Bobby Sanabria

More about Mike Amadeo

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

Afro-Cuban culture, Blog, Cuba, Latin Jazz, Puerto Rico, The Cuba-US connection, Video and audio

A Bronx Tale…

A Nuyorican, Ray Santos grew up next to a synagogue where he marveled at the sounds of the cantor, listened to Machito on the kitchen radio, and was bowled over the first time he heard Coleman Hawkins’ “Body and Soul” on a friend’s record player.

Meet the man who put the big band sound in Afro-Cuban music.

The arranger for Machito, Tito Puente, Tito Rodriguez and many others and the composer/arranger of the sound track for “The Mambo Kings.”

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

Go to Cuba with Jazz on the Tube as your guide:

Click here for details

Afro-Cuban culture, Blog, Cuba, Cuban Jazz, The Cuba-US connection, Video and audio

The influence of Cuba on American music has been pretty steady ever since there was an America to influence (Cuba is a longer European settled place than anywhere in North America.)

That said, 1930 was an especially important year. That was when “The Peanut Vendor” became a super hit in the US.

The original title of the song is “El Manisero.” It’s based on the call of the peanut vendors (“Mah-NEEEEEEEEE!”), folks you can still see – and hear – in Hanava’s Parque Central.

In 1930, Don Azpiazú and his Havana Casino Orchestra in New York recorded it for Victor Records. Sales records are spotty, but it was most likely the first million-selling record of Cuban (or even Latin) music in history.

The band included a number of star musicians including Julio Cueva (trumpet) and Mario Bauza (saxophone); Antonio Machín was the singer.

The song was such a hit that even Louis Armstrong took a crack at it, changing “Mani” to “Marie” and scatting (or proto-rapping?) on the melody.

Stan Kenton gave the piece another boost with an all instrumental version he recorded in 1947. The version here was recorded in 1972 in London.

I like this version by the Cuban group Quinteto Son de la Loma

Beloved Cuban pianist and singer Bola de Nieve (“Snowball”) offer his classic version.

To round things out, how about a version by the Skatalites of Jamaica.

The song, composed by the Cuban Moises Simons, has been recorded over 160 times and is so important to American music that it was added to the United States National Recording Registry by the National Recording Preservation Board in 2005.

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.

Go to Cuba with Jazz on the Tube as your guide:

Click here for details