Afro-Cuban culture, Blog, Cuba, The Cuba-US connection, Video and audio

Playlist

01. Introducción por Mario Bauza y Billy Taylor

02. Manteca, … con Dizzi Gillespie, 1942

03. Blen, Blen, Blen… canta Miguelito Valdés & Orq. Casino de la Playa, 1940

04. Ariñañara… Chano Pozo

05. Muna Sanganfimba…. Chano Pozo

06. Guaguina Yerabo…. Miguelito Valdés & Orq. Havanna Riverside, 1940

07. Anana Boroco Tinde… Miguelito Valdé & Xavier Cugat & Waldorf Astoria Orchestra

08. Blen, Blen, Blen.. Antonio “Cheche” De La Cruz & Orquesta Casino de la Playa, versión 1941.

09. Parampampin…. Panchito Riset con el Cuarteto Caney, 1941

10. Parampampin….. Tito Rodriguez & Marcano y su Grupo, 1942

11. Bang, Que Choque…. Chano Pozo

12. Rómpete…. Miguelito Valdés con Machito y la Afro-Cubans, 1942

13. Nague…. Chano Pozo

14. Zarabanda…. Reinaldo Valdés “El Jabao” & Orq. Hermanos Palau 1943.

15. Ampárame…. Cascarita & Julio Cueva y su Orquesta, 1946.

Fans of American jazz know about the Chano Pozo’s famous collaboration with Dizzy Gillespie, but there is much more to his life and career.

Chano was born Luciano Pozo González on January 7, 1915 in a very poor neighborhood in Havana.

In his early teenage years, he was introduced to Santería, also known as “La Regla de Ocha”, an Afro-Caribbean religion derived from the beliefs of the Yoruba people of Nigeria. He was also involved in the Abakuá secret society and Palo which has its roots in the Congo.

Pozo was a colorful, energetic character engaged in all kinds of activities, some legal, some less-than-legal, but he was best know for his drumming, dancing and the award winning compositions he wrote for Carnival parades.

One of these tunes “La Comparsa de los Dandys” is to this day a kind of unofficial theme song for the city of Santiago de Cuba and is a familiar standard at many Latin American carnivals.

Chano was involved in the battle to break the color barrier in the Cuban music industry which at the time excluded dark skinned black from professional opportunities.

In 1947, he moved to New York City for better opportunities encouraged by his friend Miguelito Valdés.

That same year he met Dizzy, recorded with him and many others, and went on tour in Europe. A year later, his promising life was cut short in a pointless act of violence on a New York City Street.

Many of the tunes on this playlist feature Chano’s friend Miguelito Valdés on vocals.

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.

Go to Cuba with Jazz on the Tube as your guide:

Click here for details

Afro-Cuban culture, Blog, Cuba, Video and audio

1. “Lo Que le Pasó A Luisita (Guaguancó)” – With his Orchestra

2. “Serende” – with Chano Pozo and the Machito and his Afro-Cubans

3. “Rumba Guajira”

4. “Mambo Abacua”

5. “Pa Que Gocen”

If you want to be conversant with Cuban popular music standards there are over a dozen Arsenio Rodriquez you must learn.

But that’s not all.

1. In an era of “plunk, plunk,” he told his bass players to make their instruments sing thus becoming one of the creators of the bass riff.

2. He put the clave back into the son after it had been gradually watered down in the 1920s and 30s.

3. He created the practice of using layered, contrapuntal parts using piano (bottom line), tres (second line), 2nd and 3rd trumpets (third line), and 1st trumpet (fourth line), all locked into the clave.

4. He invented the Latin horn section, being the first to double, then create a triple trumpet section.

5. He substituted the piano for the tres, exploding the contrapuntal and harmomonic possibilities of Cuban popular music.

6. He had his bongo player use a cencerro (‘cowbell’) during montunos (call-and-response chorus sections)

7. He included the conga in the line up of his band, the first to do so.

If his music sounds familiar and not terribly innovative, it’s because so many thousands of Latin musicians have copied from his playbook over the decades that they’ve completely normalized his revolutionary breakthroughs.

The more you know about the evolution of Cuban music in the 20th century, the more you’ll appreciate what a giant Arsenio was. And there’s a lot more than to his story that I covered here.

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.

Afro-Cuban culture, Blog, Cuba, Cuban Jazz, The Cuba-US connection, Video and audio

Machito’s son, percussionist and bandleader Mario Grillo, recalls the details of his father and his work in a touching and entertaining way.

Lots to learn from this narrative.

Machito and his Afro-Cubans perform for a live studio audience in Japan. The beautiful manners of Japan and Latin America meet.

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.

Go to Cuba with Jazz on the Tube as your guide:

Click here for details

Blog, Cuba, Cuban Jazz, Latin Jazz

Scholars are all about paper.

If it’s not on paper, it didn’t happen.

This presents are problem for future scholarship on the subject of Afro-Cuban and Latin jazz.

There’s a similar scholarship problem in the area of contributions of Gaelic to American English for the same reason.

In both cases, the people involved were so busy with the challenges of simply making a living, they didn’t have time to document and archive and mainstream society wasn’t interested in helping.

Bringing the Irish into this may seem like a tangent and in some ways it is, but not really.

Here’s why…

The word “jazz” is Gaelic.

“What?”, you say. “Jazz is an African word that means ‘sex’ or something.”

Here’s the definitive rebuttal of that nonsense

Jesse Sheidlower, editor at large for the Oxford American English Dictionary, wrote in Slate magazine, in December, 2004: “The African etymology of jazz was fabricated by the New York press agent Walter Kingsley in 1917.”

The truth is the first time that “jazz” ever appeared in print was 1913 in an account in the San Francisco Bulletin about a baseball game written by an Irish-American “Scoop” Gleeson.

Readers didn’t recognize the word so three days later on March 6th, 1913, Gleeson provided an explanation:

“Come on, there Professor, string up the big harp and give us all a tune Everybody has come back to the old town full of the old ‘jazz’ and they promise to knock the fans off their feet with their playing.

“What is the ‘jazz?’ Why, it’s a little of that ‘old life,’ the ‘gin-i-ker,’ the ‘pep,’ otherwise known as the enthusiasalum. A grain of ‘jazz’ and you feel like going out and eating your way through Twin Peaks. It’s that spirit which makes ordinary players step around like Lajoies and (Ty) Cobbs

“‘Hap’ Hogan gave his men a couple of shots of ‘near-jazz’ last season and look what happened — the Tigers became the most ferocious set of tossers in the league. Now the Seals have happened upon great quantities of it in the quiet valley of Sonoma and they’re setting the countryside on fire.”

“Pep” was a very popular word in that era, but what about “gin-i-ker?”

“Gin-i-ker” is the phonetic spelling for the Gaelic phrase “Tine Caor” which means “raging heat and lightening.”

“Tine” is the “fire” part of the phrase and it’s pronounced “Jin-eh” or “chin eh”

The Gaelic word “teas” is related to “tine”. It means “heat of the highest temperature.” In human emotional terms that would mean “hot”, “exciting”, “passionate.”

And in Gaelic the word “teas” is pronounced JASS or CHASS.

The adjective “Teasai” in Gaelic is pronounced “JASSY” and means “hot, warm, passionate, exciting, fervent, enthusiastic, feverish, angry.”

After it’s initial coining, the word “jazz” became a local verbal phenomenon in San Francisco.

In fact, an article was published it in the S.F. Bulletin on April 5, 1913 written by Ernest Hopkins: “In Praise of “Jazz” A Futurist Word Which Has Just Joined the Language.”

“Jazz” jumped the Bay and appeared in The Oakland Tribune on October 4th of that same year.

How did it get to New Orleans and the rest of the country?

That’s easy.

Every port city in the US, New Orleans included, was packed with native Gaelic speakers and first generation Irish-Americans. Many worked the docks. Many went to sea.

Many other “mysterious” slang American words come from Gaelic.

Here’s a very short list:

First the American slang, then the Gaelic root, then the Gaelic meaning.

Slum = ‘s slom e = “It’s bleak”

Cop = ceapaim = “I catch”

Racket = reacaireacht = “dealing, selling”

You dig? = Duigeann tú = “Do you understand?”

Scam = ’S cam é” = “trick or deception”

Scramm = “scaraim” = “I get away.”

“Say uncle!” = “anacal” = mercy

Buddy = “bodach” = a healthy, young man

Geezer = “gaosmhar” = wise person

Dude = “dúid” = a foolish-looking fellow based on his clothing choices

Gimmick = “camag” = trick or deceit, or a hook or crooked stick

Longshoreman = loingseoir = a maritime worker

A lot of otherwise untraceable American slang words related to labor, hardship, crime, gambling, violence and other real world, gritty aspects of life appear to have Gaelic origins.

When he died, Alex Haley of “Roots” fame was working on a book that showed the close relations between early Irish immigrants and Afro-Americans.

They lived in the same neighborhoods, worked together, dated, married, and had kids together.

What were Africans called in Liverpool in old days? “Smoked Irishmen.”

Most of the Irish who came to the US in the 19th century were from rural areas. They spoke their own language and lived a life that was much closer to tribal than modern. They were impoverished and discriminated against.

Signs on stores: “No Irish or dogs” and want ads that stated “No Irish need apply” were a reality.

In his research Haley discovered that Billy Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald had some Irish blood as did Muhammad Ali and Jim Hendrix.

History is a lot more complicated and rich than we know.

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.

Go to Cuba with Jazz on the Tube as your guide:

Click here for details

Blog, Cuba, Latin Jazz, The Cuba-US connection, Video and audio

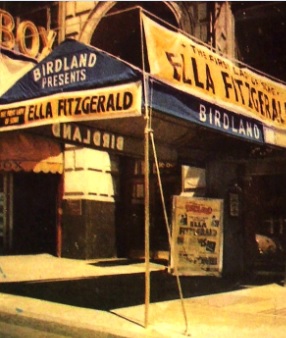

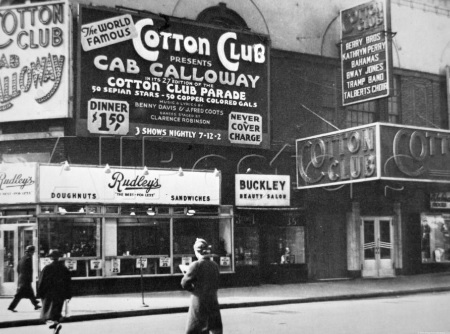

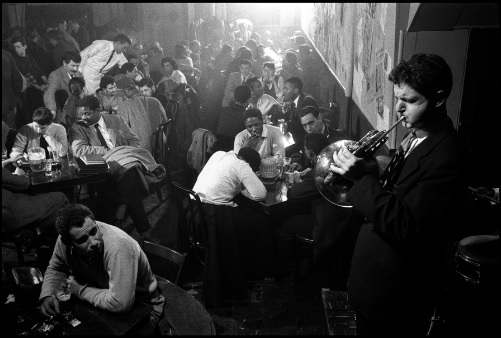

For those who missed it, Birdland, the shrine of bebop, and the Palladium Ballroom, the shrine of Latin jazz, were just a block away from each other.

The original Birdland opened December 15, 1949 at 1678 Broadway just north of West 52nd Street and closed in 1965.

The Palladium Ballroom opened in 1948 on the corner of 53rd Street and Broadway in New York City and closed May 1, 1966.

Musicians and audience members went back and forth between the two nightspots.

Jazzman Slim Gaillard and Tito Puente reminisce about the heyday – and then get down to a jam.

Note: Don’t got looking for either of these places. They’re gone, but here’s what they looked like.

The original Birdland

The front door

The front door Ella Fitzgerald in the house

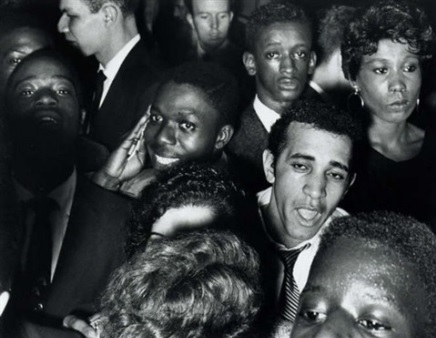

Ella Fitzgerald in the house A cool spot

A cool spot Celebrity hangout

Celebrity hangout The interior

The interior

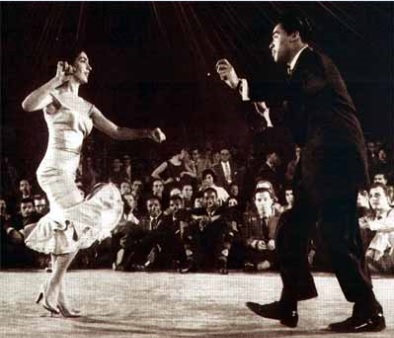

The original Palladium Ballroom

Tito Rodriguez on the bandstand

Tito Rodriguez on the bandstand The Crowd

The Crowd Tito Puente and Ray Baretto

Tito Puente and Ray Baretto Dancers

Dancers

Other famous joints

Cotton Club

Cotton Club Five Spot

Five Spot Savoy Ballroom

Savoy Ballroom The dance floor at the Savoy

The dance floor at the Savoy– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.

Go to Cuba with Jazz on the Tube as your guide:

Click here for details

Louis Armstrong

Louis Armstrong