Blog, Cuba, The Cuba-US connection, Video and audio

WKZE’s Susan Shaw, host of “Saturday Gumbo”, interviews me about the secret Cuban roots of rock and roll.

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.

Blog, Cuba, The Cuba-US connection

We’re putting a lot of time into expanding our links with Cuba following up on our trip there last March.

So many exciting things are going on, but our main focus is creating a Cuba Jazz News Service.

Believe it or not, for all practical purposes there is no Internet in Cuba. There is no country I’ve been in – and that includes Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua – with such limited access.

You can and send and receive email, but accessing the web, looking at videos, and publishing web sites from Cuba is so difficult as to practically be impossible for the average person.

Therefore the vibrant music scene there – which includes jazz of all types – is unknown outside of the country and no one “up here” reports on it.

Even Downbeat failed to include Havana’s three excellent venues dedicated to jazz in their 2016 jazz venue listings.

Certainly big name players who perform outside of Cuba are well known, but the scene on the island is unknown and unless you’re physically there, unknowable.

We’re working to change that.

Our dream is to have a correspondent in Havana who can send us a weekly bulletin about what’s happening: performances, club schedules, artist profiles, CD review, venue profiles etc.

* Horns to Havana

We’re making contacts with groups that are working with and helping jazz music education projects in Cuba.

Cuba has a world class musical education system, but there is very little opportunity for formal jazz instruction.

“Horns to Havana” which we featured recently on the Jazz on the Tube site is helping change that.

First, they’re sending instruments and parts which are in extreme short supply in the country.

Second, they’ve created an instrument repair shop in Havana.

Third, they are sending experienced jazz musicians and educators to teach in Cuba like Victor Goimes (director of jazz studies and Northwestern University and a member of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Workshop)

Fourth, they are starting to bring Cuban kids to the US to perform and be exposed to our jazz scene. A group of VERY accomplished teenaged jazz musicians were in New York City and just performed at Lincoln Center. We covered their performance at the United Palace of Arts in Upper Manhattan for school kids.

* The flash drive project

As I mentioned, things we take for granted here like casually watching jazz videos on the Internet are impossible in Cuba right now.

So how do people “access” the Internet?

With flash drives.

Someone will come to the country with a flash drive full of whatever and then it gets passed around from person to person.

We used to call this “Sneaker Net” in the days before the Internet.

Someone – and I don’t remember who – put 100 top videos such as the kind that we legally stream on Jazz on the Tube on a flash drive and gave it to a person who is central to the jazz education scene in Cuba. (Hopefully this violated no laws, but in any event I have total amnesia on the subject.)

Armstrong, Ellington, Basie, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Dizzy Gillespie, Wes Montgomery, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and a whole lot more.

As best as anyone knows, this is the first time these clips have ever been available on the island of Cuba.

We expect these “seeds” to bear fruit in the fertile soil of Cuba.

And that, by the way, is what Cuba is: Fertile Soil.

With this 50+ year trade and travel ban, we’ve forgotten the depth and breadth of the Cuban contribution to American music and the brother-to-brother relationship that American and Cuban musicians and fans used to share as a matter of course.

We’re going to do everything we can to help bring it back.

Meanwhile, pray we don’t get a crazy person in the White House next year who undoes the progress that was made this past year.

* Links to check out

Here’s the reporting we’ve done so far on music in Cuba.

Much much more is coming:

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.

Blog, Cuba, The Cuba-US connection

Before US trade and travel restrictions over 50 years ago, Cuba’s rich musical output was widely enjoyed in the US via records, live performances by “Latin” orchestras and radio. (In the early uncrowded days of radio, signals from Havana reached as far as New York City.)

American musicians (that is musicians born and raised in the US) didn’t play Cuban music itself, but they listened – and learned.

Here’s some evidence of the impact that listening had on the development of America’s most popular export Rock and Roll.

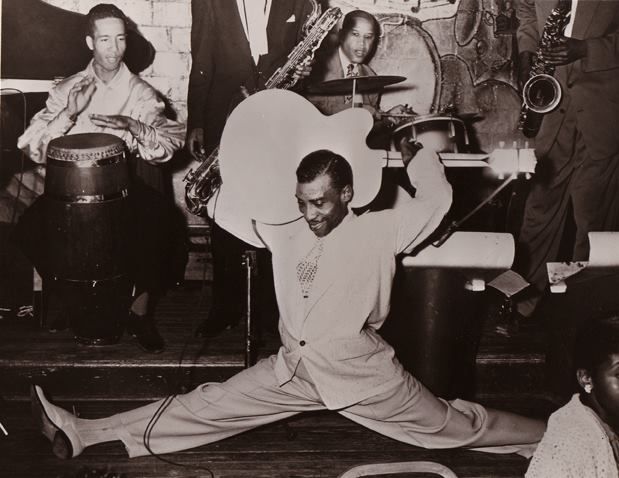

T-Bone Walker band with conga drummer

Bo Diddley with original band member and musical partner Jerome Green. It could be

a coincidence, but the maracas are a Cuban instrument and Bo Diddley’s signature

beat – 1-2-3-pause-1-2 – is pure clave

Rock and Roll Hall of Famers Dave Bartholomew and Fats Domino

“New Orleans producer-bandleader Dave Bartholomew first employed this (Cuban) figure (as a saxophone-section riff) on his own 1949 disc “Country Boy” and subsequently helped make it the most over-used rhythmic pattern in 1950’s rock ‘n’ roll. On numerous recordings by Fats Domino, Little Richard and others, Bartholomew assigned this repeating three-note pattern not just to the string bass, but also to electric guitars and even baritone sax, making for a very heavy bottom. He recalls first hearing the figure – as a bass pattern on a Cuban disc.”

– Palmer, Robert (1995: 60). An Unruly History of Rock & Roll. New York: Oxford University Press.

The figure Palmer is referring to is the tresillo, a more basic form of the rhythmic figure known as the habanera, a rhythm popularized by Cuban musicians.

“I heard the bass playing that part on a ‘rumba’ record. On “Country Boy” I had my bass and drums playing a straight swing rhythm and wrote out that rumba bass part for the saxes to play on top of the swing rhythm. Later, especially after rock ‘n’ roll came along, I made the ‘rumba’ bass part heavier and heavier. I’d have the string bass, an electric guitar and a baritone all in unison”

What Bartholomew calls a ‘rumba’ record was actually in all probability a ‘son’ record. It was and still is very common in the US to apply the term ‘rumba’ to all Cuban music.

Dave Bartholomew quoted by Palmer, Robert (1988: 27) “The Cuban Connection” Spin Magazine Nov.

If you think you’ve heard this a million times, you have. And if you’d been around in 1950, you would have heard it here first – from a US based musician that is.

Earl Palmer of the legendary “Wrecking Crew”

When he was 16, in 1941, (Palmer) stowed away on a United Fruit Company steamer for a three-day vacation on the down-low in Havana. In Tony Scherman’s oral history/biography of Palmer, Backbeat, Palmer said, “Do you realize Havana, Cuba, in 1941 was one of the wildest places on earth?—gambling and prostitution and dope all over, and music hipper than anything I’d heard to that day.” That there was somewhere with hipper music than New Orleans was quite something for a New Orleanian to admit, but then, he caught New Orleans’ big sister city of Havana at a transcendental moment in Cuba’s golden age of dance music.

Years later, when Tad Jones asked Palmer what was different about New Orleans drumming, he said, “Latin music.” For Palmer, that meant a whole set of moves that became part of his playing, sometimes dropped in with his second line stuff. He came up with ways to synthesize swinging time with the straight time of Afro-Cuban music. His metric mind-funk was essential to Professor Longhair’s 1953 recording of “Tipitina,” and he once analyzed Longhair’s playing as marking a common point between what in New Orleans was called “rumba” and the congruent Mardi Gras Indian rhythms.

– Ned Sublette Cuba and Its Music

Cuban influence on American Rock and Roll?

You betcha.

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.

Blog, Cuba, Cuban Jazz, Latin Jazz, The Cuba-US connection, Video and audio

Last week we interviewed Jana La Sorte, managing director of Horns to Havana.

Unfortunately, we missed their Jazz at Lincoln Center performance (we’ll post the video if it ever becomes available), but we did make it to their performance the next day at the United Palace of Cultural Arts at 175th Street and Broadway.

The audience were New York City school children ages six to ten, many of them bilingual English and Spanish speakers.

The orchestra played some classic numbers and arrangements by greats like Benny Carter and Glenn Miller. Then they did some Cuban numbers at which point the little ones jumped up and started dancing. This is what it’s all about.

The United Palace really is a palace. A former movie palace built in 1930, it’s been kept in

pristine condition and hosts many cultural events.

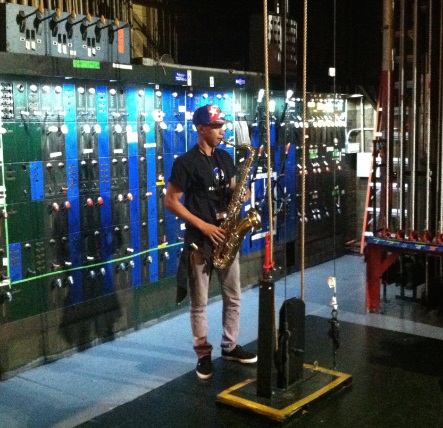

We met this young trumpet player David Navarro in Havana and were delighted to see

him again this time playing in New York. His first time out of the country.

Back stage warming up the tenor

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.

Blog, Cuba, Cuban Jazz, Jazz on the Tube Interview, Latin Jazz, People, Producer-Presenters, The Cuba-US connection, Video and audio

Interview

Download the mp3 here

Jazz on the Tube’s Ken McCarthy talks with Jana La Sorte, managing director of Horns to Havana.

This wonderful organization brings much needed musical instruments to Cuba and arranges education and exchange programs for young Cuba musicians.

For more information, click here: Horns to Havana

– Ken McCarthy

Jazz on the Tube

P.S. Our unique programming is made possible by help from people like you. Learn how you can contribute to our efforts here: Support Jazz on the Tube

Thanks.